|

|

|

I arrived back at Leeming after a week at home on leave, to find that part of Yorkshire covered in rutted ice. What a contrast to the last few months! I was greeted by Taffy and Dick Holmes but nobody else was much interested in our Libyan adventure: it was all very much of an anticlimax. I found that I had missed an AOC's parade and a Battle of Britain open day - both much to my relief. Bob Turton had been posted in from Ventnor, but was now demobbed. That was a pity, he would have liked to have known that I was still in touch with Janet.

I was soon back into the routine of shift work, but now I carried two stripes on my arm as 'Acting Corporal', after good reports reached Leeming of my work at El Adem where this acolade had been informally bestowed, mainly for the purpose of signing-off certain maintenance documents. This elevated status now turned out to be a mixed blessing as it involved additional onerous non-technical duties without extra pay, but some compensation was provided by being allowed a bed in a small room of my own. Shift work had previously managed to absolve me from Fire Picquet and Guard duties, but now I was liable for these and that of Orderly Corporal. During my final six months of service I had on several occasions to encourage tipsy people out of the NAAFI at closing time and to sit in the Guard Room through the small hours whilst the duty SP slept. The first time I did this, just as dawn was breaking, the telephone rang and a voice babbled a name and asked me to book him in, the speaker immediately ringing off. I pondered this but did not know what action to take, so did nothing. Minutes later the incident was more or less exactly repeated, only it was a different voice. On the third occasion I managed to ask the voice to repeat the name of its owner and what he expected of me. He was a boilerman coming in via the unofficial back-door of the A1 boundary fence, and I should clock him in at the machine adjacent to the Guard Room door. I did this for the first three names and for a few more people, just having to locate the appropriate clock-card, insert it into the machine and pull a lever, and then replace it in a different rack. I had never used such a device before and only realised after the first few clockings, that an additional small lever had to be moved to switch the printing to the 'In' side of the card. I never heard the result of my botched favours, but I expect the garbled clock times on their cards exposed their neat but possibly forbidden time-saving trick.

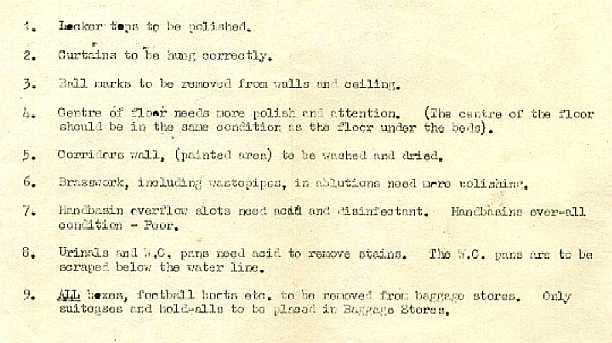

As a corporal I was also responsible for the cleanliness of my previous barrack room quarters, but my friends living therein liked to keep it clean anyway, so that was no problem at all, but if those carrying out the inspections were inclined to be 'Bull Happy' I was sometimes left with a badly typed note like this.

About that time we all had to be trained by RAF Regiment members in what we would have to do in the event of a nuclear attack. I was to be part of a team that would wander around the airfield with Geiger Counter in hand and plot the intensity of the radioactivity, marking the ground with white painted contour lines. Another training session taught us how to locate and fit the safety pin into an ejector seat in the unlikely event of encountering a crashed aeroplane. This was prompted apparently by a fatal accident to somebody servicing a plane being a little too casual in this respect , we being told that each of the aircrew sat on the equivalent of an ack-ack shell.

As the weeks ticked away I began to worry about what I might do for my living in civilian life, and studied suitable sources of advertisements. I certainly wasn't going back to Russell Acott's TV shop in Oxford: service life and the radar training had prepared me for better than that. The Section Warrant Officer tried to persuade me to sign-on for further service, but I had come to the conclusion that although it might be a good life for a single man, it was not so for a married person, and I aspired to that state. The notice board offered me the chance to leave two weeks early by receiving training at Moreton-in-the-Marsh as a fireman, but without further obligation. Another offer was to go for the last two weeks to Porton Down as a guinea-pig in the search for a cure for the Common Cold. No thank you indeed! We had heard what other research was done at that establishment, and as has been recently revealed, nerve gas really was tested on those hapless volunteers, sometimes with tragic results.

Eventually I spotted an advert in the Daily Express placed by a company called ICT (a forerunner of ICL) for 'engineers to work on electronic punched-card machines in Oxford'. I duly applied and after going to London to sit a written test-paper and an oral grilling, I was offered a job. It seemed that it did not matter that I knew nothing at all about 'punched-card' machinery, as I would receive extensive training for which my RAF training was a very suitable qualification. The pay was to be half as much again as I received in the RAF, and would be double that after a year, if satisfactory. I thought it would do very well as a stopgap while I looked round for employment with a radar company, so accepted, little realising that I would be working for them for the ensuing 36 years!

In my last week I had to undergo a thorough medical examination and thankfully it revealed that none of my experiences of the last three years had done me any harm. I suppose that some sort of celebration must have been held to mark my imminent departure although now I cannot recall where this might have been. It most likely took the form of a quiet drink in the NAAFI.

On the last day, Tony Bishop drove me to Northallerton in the section's Standard Vanguard. This at last was the greatly longed-for day, but as I sat in the train there may have been tears in my eyes as I had enjoyed those three years and I was going to miss my good friends. I pondered over the ensuing events since that first buff envelope had dropped through the door. The first impressions at Cardington, then the nervy weeks at West Kirby followed by the enjoyable and instructive months at Locking. Then the varied fortunes encountered in the putting to use of my training. I also reviewed what service life had done for me. I had met a great variety of personalities, mostly congenial but some the very opposite, and I had learnt how to live with them all. I had learnt how to accept discipline and bear a great many indignities with stoicism. I had learnt a useful trade. All these things would help me in whatever the future held and I reckoned that the three years had been far from wasted. I thought that perhaps one day I would commit my modest story to paper, and then I thought that I would probably not. What would be the point, and who on earth would be interested enough to bother to read it?

Text & Photograph © 2005 D.C.Adams

Rev251009