- RAF El Adem -

( These pages are dedicated to my two ever cheerful companions Dick & Taff who shared these times, good and bad.)

- Arrival -

As we stepped down from the air-conditioned comfort of the TransAir Viscount we immediately became acquainted with the sort of temperatures with which we would have to contend in Libya: although it was in the small hours the gentle breeze wafting over us felt as though it had originated from a hair drier.

There and then we underwent a mini arrival procedure (for such a large permanent influx was unusual), and this was conducted by clerks seemingly oblivious to the heat at tables already set up outside the small terminal building. Then we were led away to the transit tents, each of which held ten beds and the usual billet furniture. Arrayed in our beautiful blue pyjamas we made up our beds from the dusty sheets provided, and the lucky ones amongst us were soon asleep. The remainder, unaccustomed to such an environment, and not lulled by the gentle flapping of the canvas nor by the worrying occasional noises of what sounded like distant explosions, mused over the day's events before falling into a fitful slumber.

- A Rude Awakening -

We awoke to an intense all-surrounding brilliant glare. On peeping out of the tent we realised that the brightness was just how one should expect it to be in these parts at 05.00, and we hurriedly fished out the dark glasses. Surveying our surroundings more easily we could see that beyond the tents and control-tower was a thin perimeter wire fence and then open scrubby desert, whilst in the opposite direction lay the majority of the camp. Of more urgent interest was the grim concrete ablutions block which was a hundred yards away across the dusty ground and we were soon experiencing our first saline lather-defeating shower: we later learnt that water for drinking came in a ship from Malta, but water for washing purposes came from an Artesian well within the camp. The shower heads were arranged along a concrete wall, and the stalls of the lavatories in the near-by block had no doors, so there was little privacy afforded to the user of either facility. However a touch of luxury was provided by the presence of wooden seats on top of the large metal lavatory bins, but disturbingly there was no sign of any chemical fluid covering their contents.

Dressed for the first time in our new KD shirts and shorts we set out for the cookhouse in the main part of the camp. Most of the buildings we passed were of single storey white rendered construction with very small windows. The large barrack blocks were similar but each had a tall pitched roof covering four rooms, each of twenty beds. The impressive diameter of the rainwater drain pipes suggested that although rain might be an occasional commodity hereabouts its rarity might be expected to be offset by its volume. The familiar smell of greasy bacon attracted us to the correct building, but on entering we were shocked to be greeted with a huge roar of "Moon-men, moon-men, moon-men" from those breakfasters already assembled, followed by a chorus of wolf-whistles and offers of immediate over-intimate friendship. We quickly understood that this was no more than the usual El Adem greeting to newcomers, so returned the saucy banter with suitable negative rejoinders in the same style and then we were allowed to enjoy the worldwide standard RAF breakfast of tinned tomatoes and polyurethane fried egg.

- Put in the Picture -

Later, after we had packed away our 'blues' into our kitbags we were required to assemble for an inspection and briefing from our CO, Squadron Leader Craig. First it was announced that our Detachment had a title : we were told that we now belonged to 425 Signal Unit and as such one should not wear one's shorts rolled up nor one's socks rolled down: the punishments awaiting those daring to ignore this matter of sartorial exactitude would be dire. Next we were warned in all seriousness that sunburn requiring medical treatment was a crime not far short of being a capital offence, and then we were advised of the dangers of scorpion bites. An unexpected hazard was announced next: it seemed that the entire surrounding desert was a minefield left over from the war and that many of the decaying mines had become self triggering. This was the explanation for the mysterious bangs which we might have heard in the night, and therefore we would be most ill advised to ramble outside the perimeter wire.

Then he got down to business: our radar was coming in a ship but was not due for a fortnight and the other half of our contingent would arrive in two day's time. He assumed that we would not wish to continue to live in tents, hence he had organised some proper accommodation but this needed a little tidying up. We should know that we were only a temporary detachment and unlike the normal inmates of El Adem our stay was not to be of two years, but neither could we expect to be going home until events had "resolved themselves". [See footnote below]

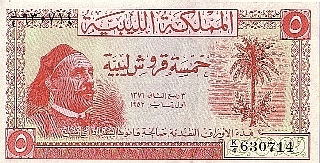

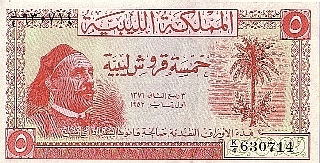

He would expect us to carry out our duties in a cheerful manner and to help put a smile on our faces we might care to know that we would be taken to Tobruk for a sports afternoon swimming in the Med whenever it could be arranged. Finally, at an impromptu al-fresco Pay Parade held outside the Station Headquarters building, we were each issued with five pounds in Libyan notes. Heartened by this unscheduled wealth, we boarded a pair of sand coloured three-tonners which had magically appeared and found ourselves being taken past the Control Tower and around the peri-track until we were at a point diametrically opposite the main camp.

He would expect us to carry out our duties in a cheerful manner and to help put a smile on our faces we might care to know that we would be taken to Tobruk for a sports afternoon swimming in the Med whenever it could be arranged. Finally, at an impromptu al-fresco Pay Parade held outside the Station Headquarters building, we were each issued with five pounds in Libyan notes. Heartened by this unscheduled wealth, we boarded a pair of sand coloured three-tonners which had magically appeared and found ourselves being taken past the Control Tower and around the peri-track until we were at a point diametrically opposite the main camp.

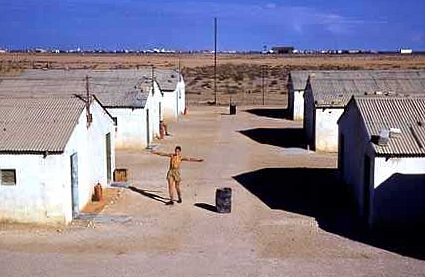

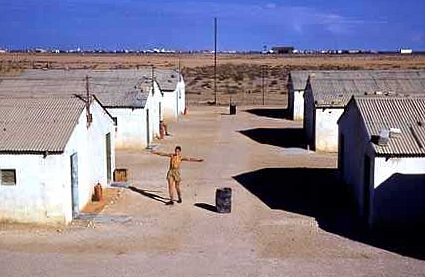

Enclosed in its own wire fence was a small village of shabby concrete huts: this was to be our new home and it was known as "German Town".

Enclosed in its own wire fence was a small village of shabby concrete huts: this was to be our new home and it was known as "German Town".

The name was apt because this was a DIY enterprise of German prisoners-of-war undertaken to accommodate themselves the better. Presently about twenty huts were occupied by civilian 'Works & Bricks' personnel. They also had a canteen building and ablution buildings, bar, games room and gardens, all of which were out of bounds to us. We later learnt that some of these people really were German and some were, almost unbelievably, original ex-prisoners who had stayed after the war to work for the British. Their little community was ruled over by a sort of 'burgomeister', the rotund Herr Ditmar. The huts were constructed from petrol tins filled with concrete and then cement rendered; the floors consisted of blue bricks with a grooved diamond pattern; the roofs were of corrugated iron sheets; the tiny 'windows' had no glass but perforated zinc sheet instead. Each pitched roof covered four rooms and each room was about fourteen feet by nine and thus would take three beds. There were enough huts to accommodate all of our airmen and NCOs but our officers would, of course, be resident in their comparatively luxurious mess on the main camp. Some huts were being used as garages for the civilians' motor bikes and some showed evidence of having recently housed their chickens and there were no 'mod-cons' at all.

- Beer, Beds and Bugs -

Having been told again that the civilian part of German Town was strictly out of bounds to us, we were shown which buildings were to be ours and supplied with brooms, buckets and disinfectant.

We set to with a will, but soon wilted in the soaring temperature. Water arrived in a one-ton bowser vehicle and we scrubbed out the huts as best we could with the yard brooms.  I bagged a room for Dick Holmes, Taffy Hughes and myself and we installed the only furniture available so far, the beds. Some civilian workers arrived and began the installation in one room of five wash basins each with a single tap plumbed to a tank which they mounted on an angle iron framework above the roof. Some native workers arrived with lavatory bins and arranged these outside behind sand coloured hessian screens. We were conveyed back to the main camp at mid-day for a meal and then we were off duty, for it was far too hot for any work at all in the afternoons. Back at German Town we just flaked out on our new pits in minimal clothing and waited for the evening to come. After a sordid saline shower it was time to return to the cookhouse, this time attired in long khaki drill trousers, for Standing Orders required this dress after 'tiffin'.

I bagged a room for Dick Holmes, Taffy Hughes and myself and we installed the only furniture available so far, the beds. Some civilian workers arrived and began the installation in one room of five wash basins each with a single tap plumbed to a tank which they mounted on an angle iron framework above the roof. Some native workers arrived with lavatory bins and arranged these outside behind sand coloured hessian screens. We were conveyed back to the main camp at mid-day for a meal and then we were off duty, for it was far too hot for any work at all in the afternoons. Back at German Town we just flaked out on our new pits in minimal clothing and waited for the evening to come. After a sordid saline shower it was time to return to the cookhouse, this time attired in long khaki drill trousers, for Standing Orders required this dress after 'tiffin'.

We were told that the camp did boast a small Astra cinema but the only other evening entertainment was provided by the NAAFI. This was housed in a low building fronted by a long verandah and was always packed with card playing, song singing, partially drunken airmen. Refrigerated tinned Watney's Pale, Watney's Brown and Carlsberg lager were the only alcoholic drinks available, each can costing 10 piastres, about the price of a pint of honest beer back at home.

Our small group staggered back around the peri track to our huts in German Town, our way lit by the incredibly beautiful starry sky and for the first time in our lives we realised what the Milky Way was all about. We changed into our short sleeved pyjamas by the light of a hurricane lamp and each put himself, his clothing and shoes into his mosquito net and tucked that in firmly around the edge of the mattress, this being standard anti-scorpion drill. The heat was still overpowering and our little room airless. We quickly found that the most comfortable way to sleep was pyjama-less but loosely covered by a sheet : those sleeping entirely naked found themselves subject to stomach cramps and 'the runs' the next day, as the temperature dropped significantly towards dawn. I should add that the close - mesh mosquito netting provided some measure of cocoon-like privacy besides its intended function of bug protection.

However, we were not protected from all bugs, for in the morning each of us found that he had suffered a trail of flea bites. Henceforward our sheets received copious doses of the Keatings Powder readily available from the stores, and this was generally effective. One morning we found a huge millipede about six inches long, dead on the floor in a spilt pool of dhobi Daz water. Our knowledgeable MT sergeant who had been in these parts before declared that we had been lucky as it had a dangerous bite.

Scorpions were never a problem, but later on we found that under the threshold slab on which we were in the habit of sitting out in the evenings, there dwelt a family of the green variety.

- An Afternoon Off-

Two nights later, in the small hours, the remainder of the detachment arrived and were conducted to their huts by the light of the stars and hurricane lamps. The following morning a Flight Lieutenant paraded the radar and wireless people and introduced himself as Technical Officer. We also had an aged W.O., a Consoles Sergeant, Kim Stanbrook as Heads Sergeant and a motley assortment of J/Ts and SACs. We were told that the delivery of the gear was on schedule and that we would be very busy setting it up in about ten days' time. Thus the next few days were spent trying to keep ourselves invisible from the hierarchy of the main camp as once the SWO knew that we had time on our hands he would be after us for guard duty and fatigues. We passed the mornings in improving our accommodation or tidying up the site, both tasks being carried out as slowly as possible. Some played darts, football or volley ball, but in the afternoons any activity in the glaring sun was just about impossible and all we could do was to 'flake out' on our beds.

One day our eagerly anticipated outing to Tobruk actually happened. Half our number packed into the backs of two sand coloured three tonners which promptly set out down the narrow traffic-less tarmac road.

The scrubby desert was all around and devoid of any features so the trip became quite boring and anyway only those at the tailgate could see what little scenery there was on view. Eventually we came to a junction known as King's Cross, joining a road that came from the direction of Egypt, but still there was no other traffic. This area was the scene of bitter intensive fighting as the Australians (mainly) successfully defended Tobruk against Rommel in April 1941. But then we came to an abrupt halt followed by a crawling progress as we negotiated a herd of wandering camels without an owner to be seen.

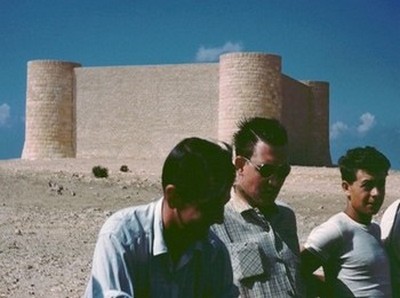

We passed the arched entrance to a large Allied cemetery, with hundreds of identical headstones interspersed with little patches of colour from straggly flowers and a glimpse of a Libyan gardener within the low wall. Finally the road passed a low hill surmounted by a large fort-like building and descended a shallow escarpment to reveal a shimmering blue inlet from the sea across which, in the haze, was a large collection of low white buildings and the minaret of a mosque.

- An Historical Swim -

The road bridged over a dry gully leading to the harbour then curved into the town passing a long low pock marked concrete wall on which was painted a line of regimental badges. On our right the rusty superstructure of a sunken ship protruded from the waters of the harbour and all of the buildings were bullet marked. The local populace was now in evidence, with an occasional donkey cart or decrepit lorry appearing. A couple of short streets with a few miserable shops set up in what looked like rows of garages, with just one or two having western type frontages, together with the mosque and a small petrol station comprised the entire centre of the town. Each of the mobile vertical tubes of black blankets seen on the pavements contained a female of the local species.

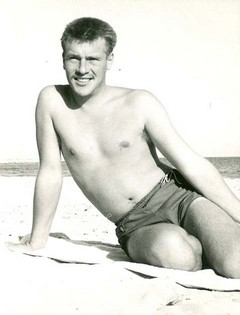

The road continued by an oil storage depot and ended on top of a low cliff overlooking dunes and the sea. A track led to a shed in a dip in the dunes and here we quickly changed into our swimming gear. Within seconds we were plunging into the Mediterranean.

That was the most delightful swim that I've ever enjoyed either before or since. The water was at a perfect temperature to cool sweaty bodies, but not too cool to chill, and was crystal clear with many yards of underwater vision but with no rocks and little vegetation. We were in and out of the water for over a couple of hours. At one point an enterprising local turned up and sold us bunches of grapes and bottles of cola all for a few piastres. Our group was the only one using the beach that afternoon.

In recent years I have read that it was probably here that in September 1942 a British commando raid (Operation Agreement) on German occupied Tobruk (Rommel's second push having taken it on June 21st. that year) should have landed, but because of poor weather the incorrect beach was marked by a submarine. The troops had cliffs to scale a few miles along the coast and so arrived late, well after the alarm had been raised by an on-time attack from inland by Commandos conveyed there by the Long Range Desert Group. The combined raid was only partially successful with many lives lost and a would-be rescuing destroyer was sunk in the harbour.

We later learnt that there was a British army garrison in Tobruk with better facilities than at El Adem, including married quarters, and that we might find some of those people enjoying this beach when we came again. Also, if we fancied a cup of tea whilst in Tobruk, there was a little cafe run by a small band of Salvation Army ladies.

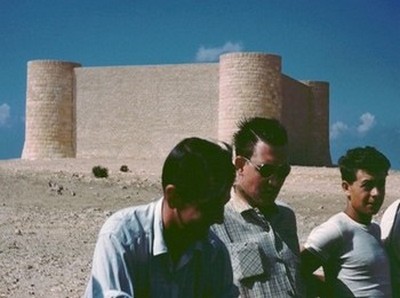

On the journey back we stopped to inspect the fort we had noticed on the hill which was in fact the German war memorial. Built on a massive scale, the cloistered interior walls were lined with bronze sheets inscribed with the names of the dead. Requiring no maintenance such a memorial should last a thousand years! An engraved text is translated as " Liver marked head the naked violence of the stars,

The battle was imposed on us and we bore the heat.

Naming names here at the place where we fought and fell:

This place is called desert - sand that shows no trace.

The desert wind was our shroud, hearts scorching in our bodies,

A storm of fate extinguished the light of our earthly days.

What we were you are, and what was imposed on us threatens you.

Learn from tracks covered over, make sure that the desert doesn't grow.

Rest in peace, German soldiers".

Stairs led to the ramparts from which was a very good view of the town :-

On the way back we spotted another roadside curiosity : the 'barbed wire brick' machine. This looked like a rusty hay baler but was in fact used to process wartime barbed wire after the local scrap industry had run out of the huge stock of ruined tanks and lorries. Unfortunately barbed wire was often used to mark minefields so now the locals had a big problem on their hands. We also saw in a depression close to the road a lorry apparently in good condition. It seems that the mines surrounding it had claimed the lives of one or two scrap merchants and now it was given a wide berth.

On entering the camp, just past the guardroom the road passed a dispersal point on which stood a well scrubbed Valetta. We learnt that this was the ultimate escape vehicle for King Idris and his entourage should his subjects become subverted by the Egyptian ruler and wish to do harm to his royal highness. In the war, Idris, who was leader of the eastern tribes in Libya did not really favour the British, but fancied the Italians who had colonised Libya before the war a darn sight less, and by implication their German allies were also on his hit list. Now the British were only there on sufferance and of course for money, but it suited our country as El Adem was an ideal staging post for the Far East and there was also a bombing range close by, which gave our war planes somewhere to practise their business a realistic flying distance from their own bases.

- More Domestic Bliss -

During these early days we explored the main camp to some degree. Insulated drinking water tanks were to be found placed at strategic intervals around the roadways but we took to carrying our small packs containing a glass bottle of water as Army type water bottles were not issued.

First, near the cookhouse, we found some superior white tiled showers which usually had hot water, and because of the enhanced lather available we dubbed these 'the fresh water showers'. Adjacent was a loo block with doors to the cubicles but the joy of these was somewhat diminished by the nature of the messages inscribed on the backs of the worthy doors.

Further afield were the hangers and the MT Section. To the rear of the latter was a huge compound containing hundreds of dead vehicles. We joked that it seemed as though the MT people never bothered to repair anything, but the true case probably was that this was the collection of over a decade and the reason they looked in such good condition was that metal took a very long time to go rusty in arid Libya. We discovered an Astra cinema, the Station Headquarters, Sick Quarters, the Officers' and Sergeants' messes , the PSI shop which sold souvenirs, a one-man barber shop, and the Radio Club.

On our rounds we frequently saw the local native labourers at work. Possibly a hundred were transported from Tobruk and back each day to do the more menial tasks around the camp. Firstly, on a daily basis they emptied all the lavatory bins into a sort of dust-bin lorry and carted the contents off to an unknown destination. They also scrubbed all the wooden seats with yard brooms. Others spent the day hoeing the various parade-grounds. Yet more collected stones to feed the gravel crushing machine which the Airfield Construction Squadron operated to provide concrete for a new runway.

These labourers all seemed to wear western type jackets but had their own style of floppy pyjama-like trousers. Their heads and faces were wrapped entirely in long dark coloured scarves. They never seemed to work very hard and were forever stopping for tea-breaks, brewing up a thick 'chai' in a tiny kettle over a fire of scrub and passing round tiny cups of the stuff. They also played a draughts type of game on squares scratched in the sand using the easily found petrified snail shells and stones as the pieces. In addition to this, whenever an individual felt the urge, he would indulge in a prayer break. Most must have been very devout as the urge came at two hourly intervals and would take at least ten minutes to satisfy. But these people were very low paid: apparently it had to be that way to avoid unbalancing the local economy as the RAF was the largest employer in the area.

But these people were very low paid: apparently it had to be that way to avoid unbalancing the local economy as the RAF was the largest employer in the area.

One old man, Mahommed Dahoud, came over to German Town every day to attend to the loos. He was always ready to do a bit of dhobi work in preference to prayer if his palm was crossed with a 10 piastre note. In this way he could easily make more in a day than he was officially paid for the whole week, and he probably became a rich man while we were there.

- Mum, it Ain't Half Hot -

Eventually we were paraded to be told the good news that the ship had docked and the bad news that it carried a deck cargo of ammunition and that we would be unloading it. Thus

early next morning, along with about forty others, and with one of our sergeants in charge, I found myself at the Bomb Dump which was located about five hundred yards from the Tobruk road about a mile from the camp. The dump perimeter consisted of triple coils of barbed wire and iron stakes, with double gates made of steel mesh. There were no buildings, but for the comfort of the armed guard there was a small tent. The enclosed area was filled with a large number of neat piles of ammunition boxes of varying sizes.

After an hour the first lorry arrived complete with a member of the RAF Regiment protruding from a manhole in the cab roof grasping a sten gun. We soon worked up a sweat and within fifteen minutes had a large quantity of boxes of 30mm Aden cannon ammunition unloaded, but within minutes the next lorry arrived. By the time the second vehicle was unloaded we were exhausted. The sun was excessively fierce and we were very thirsty. Our sergeant divided us into three shifts and for the rest of the morning we toiled for ten minute periods interspersed with breaks of twenty, although there was no shade at all in which to rest. However, periodically cold water arrived in tea-urns delivered by our Landrover. At about noon the last lorry was unloaded and only then did an Armourer flight-sergeant arrive to inspect our work. We had stacked the milk-crate sized metal boxes in very neat heaps to match the other smart piles and felt proud of the result of our exertions carried out in the incredible heat.

However there was sudden consternation. Did we not know that the Aden cannon fitted in all fighter aircraft used ammunition in left-hand and right-hand feed belts - or that it had 'use-by' dates - or that there were varying mixes of high explosive, armour piercing, tracer etc., within the belts? Could we not read? Each box had stencilled on it an exact description of its contents. So why had we so thoroughly mixed up the entire consignment of hundreds of boxes?

Nobody was required to work in the afternoons in the summer at El Adem due to the unbearably high temperature so the following morning saw us restacking the piles into mini-piles, those back into bigger piles then repeating the work and so on until it was all sorted into all the necessary categories. The mixing process had been started by those unloading the ship and compounded by those unloading the lorries. If the armourers had bothered to take charge earlier, or at least taught us how to decipher the cryptic MoD coding on the boxes, our labours would have been halved. If anything, we worked far harder on the second day doing the re-sorting. Later we learnt that we had been working through a heat wave, but exactly how many degrees that was above the hundred we were not told. Those two days were the most miserable that I have ever experienced.

One small diversion occurred during our work. We noticed a distant figure walking in across the desert out of the ever present but distant shimmering mirage. It was a Libyan youth dressed like a Khyber Pass tribesman and complete with an ancient long rifle. He begged water but only drank a mugful. He showed us his dinner kept in a pocket. It was a live desert rat and a leg had been broken to prevent its escape. The lad stayed only a few minutes then went back the way he had come. Was it possible that he was a spy?

[Footnote]

I have recently read that in July 1958 a crisis occurred in the Middle East, in which British troops were sent to Jordan and US troops to Lebanon. The crisis was precipitated by Lebanese Muslims pressing their government to join the newly created United Arab Republic with Egypt and Syria. Christian Lebanese were against this and a Muslim rebellion in Iraq toppled the pro-western government there, causing President Chamoun of Lebanon to call for US assistance. British forces were provided to bolster King Hussein's government in Jordan against pro-Nasserist forces. As a precaution 72 Squadron of NF Meteors was sent to Akrotiri in Cyprus for an indefinite period. One or more Canberra squadrons was also deployed to Akrotiri. Thus it is quite possible that it was intended that our GCI unit would move closer to the action to control these aircraft if war had broken out. As I recall it, none of this back ground history was explained to us at the time.

Return to Index...or...Continue.

Top of Page

Text & Photographs© 2006 D.C.Adams

Rev 16.10.14

He would expect us to carry out our duties in a cheerful manner and to help put a smile on our faces we might care to know that we would be taken to Tobruk for a sports afternoon swimming in the Med whenever it could be arranged. Finally, at an impromptu al-fresco Pay Parade held outside the Station Headquarters building, we were each issued with five pounds in Libyan notes. Heartened by this unscheduled wealth, we boarded a pair of sand coloured three-tonners which had magically appeared and found ourselves being taken past the Control Tower and around the peri-track until we were at a point diametrically opposite the main camp.

He would expect us to carry out our duties in a cheerful manner and to help put a smile on our faces we might care to know that we would be taken to Tobruk for a sports afternoon swimming in the Med whenever it could be arranged. Finally, at an impromptu al-fresco Pay Parade held outside the Station Headquarters building, we were each issued with five pounds in Libyan notes. Heartened by this unscheduled wealth, we boarded a pair of sand coloured three-tonners which had magically appeared and found ourselves being taken past the Control Tower and around the peri-track until we were at a point diametrically opposite the main camp. Enclosed in its own wire fence was a small village of shabby concrete huts: this was to be our new home and it was known as "German Town".

Enclosed in its own wire fence was a small village of shabby concrete huts: this was to be our new home and it was known as "German Town". I bagged a room for Dick Holmes, Taffy Hughes and myself and we installed the only furniture available so far, the beds. Some civilian workers arrived and began the installation in one room of five wash basins each with a single tap plumbed to a tank which they mounted on an angle iron framework above the roof. Some native workers arrived with lavatory bins and arranged these outside behind sand coloured hessian screens. We were conveyed back to the main camp at mid-day for a meal and then we were off duty, for it was far too hot for any work at all in the afternoons. Back at German Town we just flaked out on our new pits in minimal clothing and waited for the evening to come. After a sordid saline shower it was time to return to the cookhouse, this time attired in long khaki drill trousers, for Standing Orders required this dress after 'tiffin'.

I bagged a room for Dick Holmes, Taffy Hughes and myself and we installed the only furniture available so far, the beds. Some civilian workers arrived and began the installation in one room of five wash basins each with a single tap plumbed to a tank which they mounted on an angle iron framework above the roof. Some native workers arrived with lavatory bins and arranged these outside behind sand coloured hessian screens. We were conveyed back to the main camp at mid-day for a meal and then we were off duty, for it was far too hot for any work at all in the afternoons. Back at German Town we just flaked out on our new pits in minimal clothing and waited for the evening to come. After a sordid saline shower it was time to return to the cookhouse, this time attired in long khaki drill trousers, for Standing Orders required this dress after 'tiffin'.

But these people were very low paid: apparently it had to be that way to avoid unbalancing the local economy as the RAF was the largest employer in the area.

But these people were very low paid: apparently it had to be that way to avoid unbalancing the local economy as the RAF was the largest employer in the area.