At the end of our third week at Locking we were allowed home on a '48', which meant that we could travel home early on Friday evening and had to be back to start lessons on the Monday. A normal '36' weekend allowed us our freedom only at 1300 on the Saturday, and then most chose to remain on the camp. A Saturday routine evolved which was to take a late afternoon mixed grill in a nice little Weston cafe we had discovered, followed by a visit to the cinema, or alternatively and exceptionally to visit a Bristol professional football match and then a pub. On Sunday we tended to just fritter the day away around the camp in order to save money, but later, weather permitting it would be the day for a motorcycle ride much further afield.

Our very first outing to a pub in Weston deserves a mention. Several of us knew that Somerset was where cider came from and we were all keen to sample the local 'rough stuff'. So a group of us went into the first pub we encountered and ordered pints of 'Scrumpy'. The landlord quite obviously took in our youthful appearance because he suggested that perhaps we should start with half pints instead as Scrumpy was not to everyone's taste and he would hate to see it wasted. He was right, it was not as sweet as beer, in fact sour almost, and it seemed very watery although it did taste vaguely of apples and indeed tiny bits of some part of an apple tree floated in it. However eventually we all got it down and loudly agreed that it was 'great', but nobody suggested a second round. The initial stagger as we we got up to leave caused us to immediately understand the cause of the fame of the stuff. It had gone to our legs and without exception we all lurched causing us to realise the true reason why the sensible landlord had been reluctant to sell us full pints.

Our very first '48' presented us with a problem, as there was a national shortage of petrol (which I believe coincided with difficulties in travelling by rail). However, along with many others I decided that I would attempt to hitch-hike home, as I intended to return on my motorcycle. A bus took us to the main road to Bristol and there we tried our luck with the limited passing traffic. There were many men in blue waiting for a vehicle to stop, but we were lucky in those days in that men in uniform were treated with sympathy when 'hitching'. A large brewery lorry returning to Bristol provided the first lift for about ten of us and we had to sit in the back with the barrels. Another bus in Bristol took me to the Swindon road where a Burton's tailor's van took me on to Swindon sitting amongst rails of dangling suits. The final third of the journey saw me sitting amongst crates of empty bottles that had contained blood, for I was in a vehicle returning to the Oxford Blood Donors' unit.

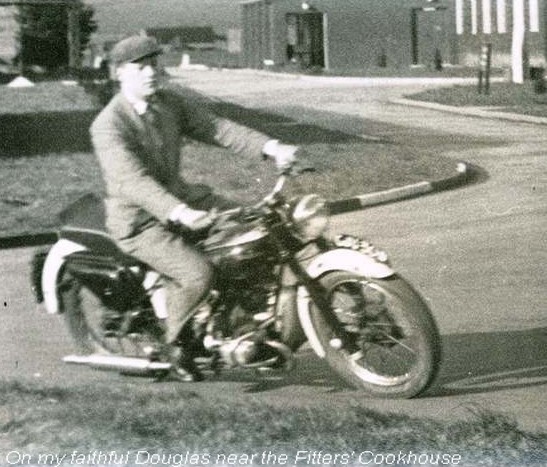

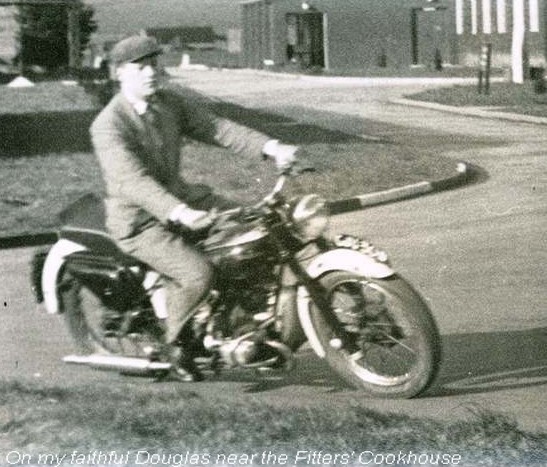

The five gallon petrol tank on my Douglas was nearly full, enough for over three hundred miles, so I set off happily on Sunday afternoon for the return trip. My longest previous outing on the bike had been only to Henley and back, about forty five miles, but now I had a hundred to cover. But all went well, the lack of traffic now a benefit and the worst part was finding my way through Swindon and Bristol, otherwise it was merely a matter of cruising at 50 mph on country roads. Two of my colleagues returned on motorbikes that weekend too, one from Birmingham and the other from Kent.

My longest previous outing on the bike had been only to Henley and back, about forty five miles, but now I had a hundred to cover. But all went well, the lack of traffic now a benefit and the worst part was finding my way through Swindon and Bristol, otherwise it was merely a matter of cruising at 50 mph on country roads. Two of my colleagues returned on motorbikes that weekend too, one from Birmingham and the other from Kent.

On the Monday, before our first lesson could start, one man had to report to the 'Headmaster' officer i/c Fitters' training. This bod had been a County class Rugby player before he was called up, and he now played for the RAF Locking team. He returned with a smile on his face and reported to our instructor Pilot Officer that he was to be backclassed. Not for any lack in absorbing the training, but due to his ability at his sport. RAF Locking was planning to hold on to him at least until the Rugby season ended, and there was some prospect of him completing his two years at the camp in a sinecure 'assistant instructor' capacity.

Our training in Basic Principles moved on to those of Electronics but this subject was renamed as 'Fundamentals'. Witty Dave Flux from Portsmouth immediately declared that it meant we were now very much 'in the clag', and that 'Semper in Excreta' would henceforward be our class motto. Dave had earlier provided us with a class song. A popular song of the time was 'Freight train, freight train, goin so fast...' and Dave subtly modified it to the more technical 'Phase Change, phase change', goin so fast..., and we went around humming that. Initially I found myself on much safer ground as I had been studying electronic principles in an amateurish way since about the age of twelve. My interest started because my brother's hobby was Wireless. He was jolly good at it and having started off from a birthday gift of a crystal set he progressed to the point where he constructed an excellent three valve battery 'straight' set from a Sparks Data Sheet which worked so well that it was used as the family receiver for several years. My brother regularly bought new books on radio and he also took the monthly Practical Wireless magazine. Naturally my curiosity was aroused and I benefited from this ready source of free educational material. Hence I found out for myself how valves worked as far as radio went, but I also knew how they could be employed in a television receiver too, as my brother's most ambitious project was to build one using modified government surplus units and a six inch cathode ray tube with a green phosphor.

So valve theory was relatively easy but in addition many electronic concepts which I had previously only half understood were now properly explained to me. After a couple of weeks of achieving high marks in the tests, the name of what we were studying changed yet again: it was now 'Radar Fundamentals'. This of course was a new field for everybody and as we ploughed through RF, and in particular Centimetrics, the only man to get high marks was the one with the photographic memory. Fortunately for me maths did not now seem as necessary as before, but it was still very necessary to chew over a day's topics in the evening. All this mutual self-help also served as a prolonged bonding exercise, with everybody genuinely wanting everybody else to get through. At the final examination for this module I scraped through with a score in the low seventies, but one of our number was not so lucky and when he was duly back-classed and moved out of our hut, we were saddened and missed him for a while.

'Bull' at Locking was a far less important thing than it had been at West Kirby. Nor do I recall that we were ever required to undergo a kit inspection. Our hut was supposedly inspected every Friday and consequently Thursday evening was partially spent in sweeping, dusting and polishing everything up including the ablutions. We did not polish our boots very much except before a monthly whole-camp parade. This involved the Fitters' Squadron assembling on our local 'Bellman Hangar' small parade ground before marching to a larger space where we would join up with Squadrons from the Mechanics and from the Apprentices. I remember an occasion when this initial forming up was done in a thick fog. There came a point in the familiar routine when each Flight in turn was required to confirm its presence, when the officer leading the parade would start by shouting out, 'Are you there Number One Flight?', in expectation of the reply 'Number One Flight present, Sir!' For the very first time I could see that this was not an unnecessary and silly question, for on this occasion, although we could see some of the adjacent flight, in the swirling mist we could see neither all of it, nor the officer expectant of a reply. Marching at Locking was not always the same as marching at West Kirby, for on the way to the main parade ground we all contrived to march in the sloppiest manner we could get away with, but once there we had to smarten up somewhat as we were required to march round in performance of all the usual pointless evolutions until one Squadron or another would be formally inspected by Group Captain Blair-Oliphant, our Station Commandant. He was a man of many medals and especially to be respected as he had been a British sabres contestant in the Olympics. Finally our Wing Commander Padre would offer up a few prayers, but not before the order came 'Fall out the Catholics and Jews'. This order always caused me mild amusement as it conjured up in my mind a religious 'punch up' ensuing at the edge of the parade ground as we dutifully prayed for peace in the centre.

My longest previous outing on the bike had been only to Henley and back, about forty five miles, but now I had a hundred to cover. But all went well, the lack of traffic now a benefit and the worst part was finding my way through Swindon and Bristol, otherwise it was merely a matter of cruising at 50 mph on country roads. Two of my colleagues returned on motorbikes that weekend too, one from Birmingham and the other from Kent.

My longest previous outing on the bike had been only to Henley and back, about forty five miles, but now I had a hundred to cover. But all went well, the lack of traffic now a benefit and the worst part was finding my way through Swindon and Bristol, otherwise it was merely a matter of cruising at 50 mph on country roads. Two of my colleagues returned on motorbikes that weekend too, one from Birmingham and the other from Kent.