|

|

Abrupt were the farewells as my train pulled out of Bristol's Temple Meads station, leaving behind the ever decreasing group of my good friends of the last eight months as it dispersed to individual postings across the Empire. Little did I know at that moment that my own destination was to become for me a very special part of the realm, nor that my time there would affect and benefit the whole course of my life.

A few days earlier at RAF Locking, our radar training school near Weston-Super-Mare, when the postings had been announced to our newly graduated class, Dave Flux who was from Portsmouth had doubled up with hysterical mirth, chortling

"

The old paddle steamer was a novelty to me, as was the short voyage on the mercifully calm sea and likewise the awaiting antique tank engine which trundled its little train asthmatically and unhurriedly through the sleepy green countryside to Ventnor. A short ascending taxi ride and there I was at the door of the miniscule guardroom of yet another novelty : No.23 Signal Unit surely had to be the smallest RAF camp in the land.

The few single storey buildings were disposed on either side of a single hundred-yard road, the whole camp being on the right hand side of a deep grassy valley, the route of the road from Ventnor to Wroxall and Newport forming the western periphery of the site. Most of the expected edifices were present but each was amusingly Lilliputian compared with those at Locking. I found later that Ventnor was in fact administered from RAF Sopley which was about thirty miles away near Bournemouth on the mainland. The red-brick hut, number 29a, to which I was directed was at the far boundary adjacent to the Wroxall road. It had two rooms each with three sets of bunk beds, one room with two beds and a Corporal's room. In the ablutions section, rather strangely, I found each of the three wash basins to be in a cubicle.

This photo taken by Roy Eames looks back to the main gate and beyond, and gives some idea of the small size of the domestic site and its picturesque sloping location. The diminutive NAAFI and Cookhouse are on the left and the Sergeants' Mess and Sick Quarters on the right. The airmens' huts were mostly to the rear and to the left of this viewpoint. The lower slope of St. Boniface is in the background, also civilian housing. (See Camp layout)

Suddenly the hut was full of the returning afternoon shift and I was greeted pleasantly by Corporal Lefty Collins. They were expecting me: I was to replace one of their number who was being demobbed tomorrow and I should come down to The Prince tonight for his demob party as this would be a good way of getting to know the boys. I warmed to this instant acceptance and readily agreed. When I commented on the RAF's unusual concern for the modesty of its airmen at Ventnor, the explanation was "This is a WAAF's billet" which momentarily caused me to think that perhaps my luck was about to change! That is until I was laughingly enlightened : there were none presently at Ventnor hence we could live in this abnormally civilised accommodation. I made a casual remark about Type 54s and got a puzzled reply - there were no Type 54s, the towers belonged to the prehistoric wartime CH gear, long since out of use. My heart sang as this great worry was lifted! Life was going to be good at Ventnor. Soon I found myself with this happy gang in the diminutive cookhouse, crowded with a mere fifty or so diners. There was no long queue and the food was served by civvies, one of whom was dodging about answering calls for more bread and condiments. The bread was chunky local baked, a far cry from the usual Mother's Cardboard, and the food almost like home cooked. Air Force life really was looking up. Later we strolled in the evening sun down The Shute and narrow steep roads to the town. The Prince of Wales was the adopted RAF pub and the party went well, but I felt a stranger so crept away after a couple of beers and left them to it.

I went down to see the seafront and then slowly climbed back to Lowtherville in acknowledgement of the call of my bed after the tiring day. However, to my annoyance I was awoken at about two a.m. by the clamour of raised voices. The room was full of my new comrades and others, and to my horror two Service Policemen. It transpired that after the lads had left The Prince at closing time a lot of horseplay had taken place near the beach. As I had not yet officially 'arrived' on the camp my presence perplexed the SPs as they were unable to recognise me and this allowed me to lead them on to quiz me at length, thus somewhat alleviating the pressure on my new colleagues. The outcome of this escapade was that minor punishments were awarded to the unfortunate few up before the CO in the morning. I thanked my lucky stars that I was not one of them. What a start that would have been, to have been on a charge when not having even arrived! The local newspaper carried a half column report of this disgraceful saturnalia but our good relationship with the town was but briefly tarnished. This mainly involved water battles on the boating lake, but one lad had managed to start a mechanical excavator (the very one shown to the left) which was on the beach, although he had not been able to coax it into motion. An indignant burgher had called the civilian police who together with the SPs had tried to apprehend the tipsy crew but the ways from the front up to Lowtherville are several and various and could not be entirely guarded by the four police so few were caught. Hence all those abed had to give account of themselves and undergo a simple breath assessment.

This mainly involved water battles on the boating lake, but one lad had managed to start a mechanical excavator (the very one shown to the left) which was on the beach, although he had not been able to coax it into motion. An indignant burgher had called the civilian police who together with the SPs had tried to apprehend the tipsy crew but the ways from the front up to Lowtherville are several and various and could not be entirely guarded by the four police so few were caught. Hence all those abed had to give account of themselves and undergo a simple breath assessment.

My trance was broken by a shout from a portly Warrant Officer who required me to accompany him into 'the bungalow' and into his office where he interrogated me in avuncular fashion as he issued me with a fitter's tool box, the contents of which had to be checked and signed for. The SP at the security barrier swapped my 1250 identity card for a brass token and only then was I allowed to follow the WO down the spiral stair and along the highly polished brown linoleum floor of the surprisingly long ever descending corridor. Having passed a wall-mounted glass fronted case containing a pair of pistols (the bullets for which were kept in the safe in the office above), the corridor turned a right-angle to the left and continued for about another thirty yards still descending, until we reached the massive blast doors. We were in 'The Hole'.

I was handed over to a Corporal Lewis who sat at a desk in a corner of the Radar Office. I judged him correctly to be an ex-apprentice as he was not much older than myself and he welcomed me cheerily

onto his shift. Lewis took me on a guided tour of the extensive underground set-up and I was most impressed as my world was 'Rotor' and I knew nothing at all about the 'Consoles' gear. However, I found

it all very claustrophobic and was heartily glad that I was to be employed above ground and so was relieved when he led the way back up to the wonderfully fresh air and across the hundred yards of gorse

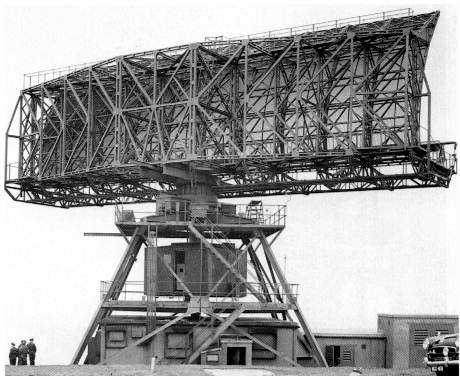

to the unsleeping monster that was generally known as 'The Eighty'.

While I absorbed the unanticipated noises of the machinery, a muffled roar from the alternator room, a whine from the turning-motors and above all a wafting hiss as the seventy foot reflector sliced through the summer breeze, Lewis rang the bell at the armoured always locked postern door. From within a dishevelled ginger-haired LAC mechanic unlocked the door and admitted us to the inner sanctum, a 20 foot square room beneath the straddling legs of the main structure. I later found that Ginger didn't much care for being in the RAF but as with a lot of the National Servicemen in the Radar trades, he was very bright. In keeping with his geekishness he spent most of his shifts perusing the Air Publications and I soon found that he knew the workings of the gear at least as well as any sprog fitter.

After a brief inspection of the modulator, the purpose of which was to produce extremely short pulses of extremely high voltage, I was shown the Signal Office Diary, the Meters Records book and the Standing Orders. Then we went out, clambered up the iron stairs to the gantry and with some agility leapt on to the running board of the rotating transmitter cabin. Walking across the floor of this 12 foot square room made one stagger as though inebriated. A grey cabinet contained the true heart of all this equipment, the watercooled magnetron which, fed on the diet provided by the modulator below, produced enormous 2 megawatt microwave incredibly brief pulses of 2 microseconds duration, spread evenly 270 times throughout every second of every hour. These colossal bursts of energy were cunningly directed by means of highly scientific piping known as 'waveguide' to the focus of the giant reflector which formed their energy into a narrow electro-magnetic beam and directed it away into the atmosphere. As soon as each pulse ceased, the waveguide from the aerial became joined by electronic means to the receiver kit. Any one of those huge pulses hitting a distant target caused a re-radiation from it of greatly diminished energy, part of which which 'bounced' back to the reflector. Collected by the waveguide it was then amplified and passed on to the underground consoles where it would be depicted as the new bright head of a tiny orange tadpole (of slowly decaying previously received pulses) which swam incredibly slowly across the radar screen.

This radar could "see" reliably targets 250 miles away and sometimes at a greater distance if they were very high fliers. This was state-of-the-art Early Warning, incredibly better than anything used in the war years and of unrivalled precision. However our Type 13 height finders, although they could see targets at 50,000 feet, could in no way match this range as they dated in design from the middle of the war.

As we descended, Lewis told me that there was one other 'R' member on our shift, an SAC who was presently on leave. Lewis was 'C' himself and had an SAC and LAC to help him sort out any subterranean disasters, so the total shift strength was six. That was all that happened on the first day: on all subsequent ones I would be a key member of the team and have to accept the responsibilities for which eight months of intensive training at Locking was supposed to have provided adequate preparation. Amazingly this prospect did not dismay me at all, on the contrary, I was thrilled. I was young and optimistic and indeed, felt it a great privilege to be allowed to have the run of this amazing million pound machine, and by so doing carry out my part in helping to guard the nation. Honestly I really did : you see at that time we had all been brought up in the scary shadow of possible imminent atomic warfare.

After demob, Michael (Lefty) Collins worked at the Saunders Roe Black Knight rocket test firing facility at The Needles. He lives on the Island.

Text © 2006 D.C.Adams

Rev080519