|

|

Shiftwork can be an onerous duty, but a lot depends on the way in which the work periods are organised. At Ventnor the cycle included a session of four nights followed by a sleeping day and then three clear days off duty. It was often possible to get one's head down for a few hours during the night shift and if so the next day was not to be wasted in sleep.

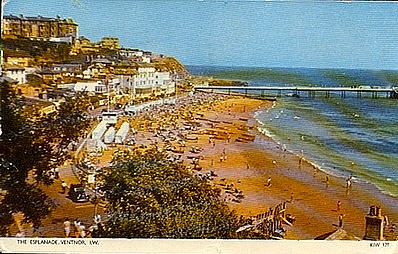

Ventnor is blessed with a small but pleasant beach and throughout the summer there were weekly changes of holiday makers, a proportion of whom were girls of our own age.

I include at this point a picture of our most eligible bachelor hero caught here employed in the mundane domestic chore of darning his sock, but no doubt he was contemplating the possibilities that an evening out in Ventnor might hold in prospect. Perhaps he would even meet up that very evening with she who one day would forever darn his socks? Under the tutelage of Chas, a consoles mechanic on our shift and an expert in such matters, I learnt that the first principle of any attempted wooing (or seduction) was not to reveal one's identity as RAF personnel, and the second always to use an assumed name. However, as such deceit was alien to my nature I was unable to employ such a dubious strategy and consequently can report little more than cheerful beach repartee and a rare kiss and cuddle in the evening darkness on the cliff path to the west of the town.

I include at this point a picture of our most eligible bachelor hero caught here employed in the mundane domestic chore of darning his sock, but no doubt he was contemplating the possibilities that an evening out in Ventnor might hold in prospect. Perhaps he would even meet up that very evening with she who one day would forever darn his socks? Under the tutelage of Chas, a consoles mechanic on our shift and an expert in such matters, I learnt that the first principle of any attempted wooing (or seduction) was not to reveal one's identity as RAF personnel, and the second always to use an assumed name. However, as such deceit was alien to my nature I was unable to employ such a dubious strategy and consequently can report little more than cheerful beach repartee and a rare kiss and cuddle in the evening darkness on the cliff path to the west of the town.

Thus unhappily for me the more usual social programme that evolved was to follow the afternoon on the beach with an evening of drinking and darts in either The Prince, The Rose or The Hole in the Wall, always ending up in the Lugano coffee bar on the esplanade where the talk was invariably of girls, real or imaginary. On Saturdays there was often a dance at the Winter Gardens in Ventnor or at the Trouville Hotel in Sandown and many of the lads found girlfriends in this way. Bob, a highly strung wireless mechanic went to the dances and often reported his conquests but it was generally believed that he was a terrible line-shooter. Some of the blokes used to think that riding the dodgems at a rather seedy and horribly noisy establishment off the Promenade, was fine fun and a possible meeting place for girls, but neither the associated fair-ground din nor the majority of the type of girls frequenting it appealed to me. (See note below.)

On Saturdays there was often a dance at the Winter Gardens in Ventnor or at the Trouville Hotel in Sandown and many of the lads found girlfriends in this way. Bob, a highly strung wireless mechanic went to the dances and often reported his conquests but it was generally believed that he was a terrible line-shooter. Some of the blokes used to think that riding the dodgems at a rather seedy and horribly noisy establishment off the Promenade, was fine fun and a possible meeting place for girls, but neither the associated fair-ground din nor the majority of the type of girls frequenting it appealed to me. (See note below.)

For some however, things were on a higher plane. Steve, a personable consoles SAC, found true love and became engaged to Shirley, an attractive Ventnor girl.

Other activities involved the use of my motorbike which I had brought across at the first opportunity and which allowed me to explore the Island thoroughly and to swim from other beaches. Lefty Collins owned a pre-war Morris Minor, a car usually mistaken for an Austin Seven. On one glorious summer's day I persuaded him to drive completely around the Island and the ancient car managed the seventy miles without any problems at all.

Meanwhile, back at the top-site, there was our duty to be done. Britain had to be guarded whilst it slept.  The night shift started off at eleven o'clock by piling into the back of the three-tonner for the short ride to the top-site during which we were able frequently to admire the unforgettable sight of the brilliant moon cutting a wide swathe over the inky sea. Then for me the night-bind often meant enduring the shift in the noisy interior of the 'Eighty'. After taking over from the evening man I had to record in a book the readings of about fifty meters and gauges, each of which indicated the state of health of some vital unit. This had to be done two hourly and the idea was that faults could be pre-empted by spotting any slow deviations from normal. This scheme could be spoilt entirely by any lazy individual who merely copied down the previous readings, and this was frequently done by some. Thus it sometimes transpired that it was I who was first to notice an irregularity.

The night shift started off at eleven o'clock by piling into the back of the three-tonner for the short ride to the top-site during which we were able frequently to admire the unforgettable sight of the brilliant moon cutting a wide swathe over the inky sea. Then for me the night-bind often meant enduring the shift in the noisy interior of the 'Eighty'. After taking over from the evening man I had to record in a book the readings of about fifty meters and gauges, each of which indicated the state of health of some vital unit. This had to be done two hourly and the idea was that faults could be pre-empted by spotting any slow deviations from normal. This scheme could be spoilt entirely by any lazy individual who merely copied down the previous readings, and this was frequently done by some. Thus it sometimes transpired that it was I who was first to notice an irregularity.

The Type 80 could not be shut down lightly - it was the reputation of the site at stake - so once or twice I spent the entire shift gazing at a particular meter praying that its needle would sink no lower. In the morning the matter could be reported to the Warrant Officer and the responsibility would no longer be mine: he could arrange for the temporary shutdown and for the blind spot in surveillance thus caused to be covered by a neighbouring mainland radar site. I quickly developed the ability to sleep on any floor, and with my head comfortable on the make-shift pillow of my tool bag and folded padded jacket, I would cat-nap stretched out in front of the modulator. It had to be in that exact spot as this unit suffered from a vice known as 'tripping'. This was an over critical safety feature designed to prevent serious internal electrical damage but would often come into operation spuriously. When tripped the Type 80 was blind and there was a ten second period in which to press a reset button to restore modulation and prevent a more drastic shutdown sequence being automatically initiated.

The operations staff would not notice the loss of signals during the ten second period but all hell would be unleashed if the trip was not reset, as several minutes would be needed to recover from the full shutdown. From my chosen sleeping position I could easily reach up to the button and this system never failed: the trips would happen and though probably still asleep I would reset them. However, my trusty alarm clock would awake me for the next meter reading session.

The R members of the shift shared the Type 80 duty equally so the other man would spend the night in comparative comfort, asleep on the floor of the carpeted offices underground and only awakened if a faulty Type 13 should demand his services. But he was required to venture out at 06.00 to visit each height finder in turn to carry out Daily Routine Maintenance. I loved to do this as it was a beautiful time to be out and  about on St.Boniface tramping through the dew with only rabbits and skylarks for companions.

about on St.Boniface tramping through the dew with only rabbits and skylarks for companions.

This daily maintenance was pretty undemanding, but was very necessary. The received signals could be increased a little by dint of careful tuning. This was achieved by hand cranking the cabin around until the aerial was on the exact bearing of Cherbourg. Then, whilst watching the received echo on the A scan monitor, tweaking one or two controls until the small signal from the radar reflector on top of Cherbourg lighthouse was clearly discernible and at maximum amplitude. If this was not done efficiently the operators would complain of poor or non-existant returns from the more distant of aircraft targets for the rest of the day.

Occasionally life was more exciting. Once, by some chance I did the Type 13 maintenances as well as having spent the night in the 'Eighty'. Thus I had not read the Shift Diary kept down below in the Radar Office which explained that a new magnetron fitted in one of the Type 13s was producing 50% greater output than normal and as we were waiting for the cracked flexible waveguide to be replaced on this head, power must be limited to the correct 500kW. I duly did the maintenance which as always included turning the variac up to maximum and I was impressed by the power produced, but not perturbed as I had seen 25% above normal with other magnetrons. About two hours later, in bed, I heard the fire engine go by and at lunch the cookhouse was abuzz with chat about the fire in the Type 13. I quaked and fully expected the outcome would be a court martial. When I arrived for the next night shift I was hugely relieved to find that scapegoats were not being sought. All that had burnt was the external rubbery pitch material on the flexible waveguide which had ignited because the energy escaping through the crack had set alight the bone-dry canvas weather sleeve which was laced around it. I think I escaped unscathed because more senior people had not expedited the replacement of the cracked flexible and they could hardly pillory me without highlighting their own indolence.

On another occasion I escaped with just the rough side of the WO's tongue when I deserved worse. I was required to clean the slip-rings of a Type 13 as the received signals were noisy and happily went off with petrol-no-lead and lint free cloth. I had not done this job before but did not foresee any problems. I clunked off all the circuit breakers on the wall of the plinth and all went silent as the scream of the amplidyne ceased. I clambered up into the cabin and undid the clips of the curved plates which covered the slip-rings but as I removed them I accidentally let one fall onto one of the brass rings. There was an almighty flash and the stench of ozone. As I was bemusedly considering the ramifications of my carelessness, the telephone rang urgently. It was the WO. What the hell was I doing exactly and did I realise that I had put the whole station off the air? And would I care to join him in the Plant Room and provide an explanation? And at the double. As I trotted back down into the hole, it occurred to me that the uncaring man had not enquired as to the state of my health.

I found him with Sgt.Attril just finishing the replacement of the large fuses in the 180 volt 500c/s system. It transpired that the circuit breaker to isolate this supply to my Type 13 was illogically and inconveniently located down here, underground. In reality the whole station was not incapacitated at all as the Type 80 remained operational, but all the height finders and the Type 14 low level radar were out of use for half an hour or so. Of course I was the one who had to race round and power them all up again. However, my credit must have been good because that was the end of the matter, but I felt very silly for a few day and had to live with wisecracks from my colleagues for much longer.

Another incident did concern the Type 80. In the middle of one night I awoke from my recumbent posture in front of the modulator but it had not tripped. Instead as I quickly realised, the room was full of smoke, but I knew from the various noises that the transmitter was running and the aerial rotating. After a few seconds of blind panic I discovered the source was the turning gear control cabinet. I ran to the phone and asked the SP on duty in the Bungalow to cancel any fire alarms and optimistically assured him that everything was under control. I ripped off the upper cover of the unit and found the cause to be a still smouldering coil on a large contactor controlling one of the motors. I knew it was possible for the aerial to rotate using one motor only if the wind speed was low enough, so slowed the speed of rotation then switched off the circuits for the offending contactor and then cautiously increased the power on the other motor. Back at four rpm, the meter showed the motor current was peaking disturbingly high, but these currents often did if the huge reflector encountered a particularly violent puff in gale conditions.

My next action after opening the exterior door to aid ventilation was to phone the officer in charge of the Operations Room. He had of course no inkling of my little drama as none of his operators had yet noticed any temporary variation in the speed of rotation of their consoles' traces, but after considering my report briefly, he agreed to slow rotation to 2 rpm at which speed the motor currents would be back in the safe zone. The outcome of all this was that the next day I was complimented for doing the all the right things, but of course I had not revealed that I was asleep on duty when the burning started.

I had cause to slow the Type 80 again when one night a full gale blew up. The wind was so fierce that I could only make progress from the bungalow to the Type 80 by crawling crab-like, low to the ground. Later in the night the gale intensified and the motor currents were going berserk with the structure making agonised creaking noises as the reflector came across the wind. I went out to see what was amiss and could hardly believe my eyes. Imagine the reflector as the beam of a see-saw : now imagine the huge reflector see-sawing as it rotated. It shouldn't have been possible but it was happening. I made an impassioned plea to be allowed to reduce speed and all returned to normal at 2 rpm but no one fully believed what I had witnessed. [ Note:Two Type eighties in the Scottish Islands were damaged by gales and in each case the reflectors were smashed. As the reflector was constructed in three sections, what I saw must have been the two outer sections flexing in anti-phase.]

It was during a thunderstorm that a rather remarkable event happened and it is one which many find difficult to believe. It was not to do with machinery, but about an Alsatian guard dog. Two dogs were kept at the Ventnor top-site where they lived in kennels within a small compound to the rear of the bungalow. Their handlers had an easy life and usually seemed to work days, when they made the presence of the dogs obvious to the passing public. Thus on the night of the storm neither handler was on duty when I returned soaked at the bungalow and mentioned to the SP that the dogs were making a fearful racket. We both went out to talk to them and the Boxer more or less settled down but the Alsatian would not be pacified so the SP phoned the handler who suggested that we should bring the dog in out of the storm. The SP knew the dog quite well but he found it very tricky to leash the animal as it leapt violently and redoubled its barking at every lightning flash, even when he eventually got it into the guard room. He reported to the handler that it was still distressed, and this is the amazing bit: the handler whistled loudly into the phone at his end, and the dog heard it and stopped barking instantly. The whistle was repeated and the dog stood rock still, ears cocked, obviously awaiting an order. Next the SP was asked to put the phone near to the dog's head and the handler spoke to it for about half a minute. Then the dog walked over to a corner of the room and settled down on the floor; he did not put his head down but remained looking expectantly at the door and seemed more or less oblivious to the storm which still crashed on. Ten minutes later the handler arrived and stayed for the rest of the night.

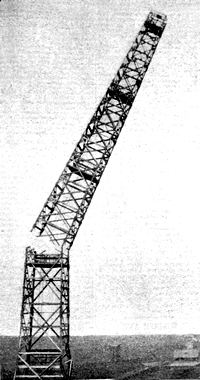

Another notable event, and indeed one notable in the history of the radar site was the dismantling of the CH towers. One Monday morning in July, a gang of civilian workers arrived and like spiders ascended the first steel pylon. Soon nuts and bolts were raining down and then one by one the lengths of steel were lowered. Some of the steel girders were sold as scrap and a local sheep farmer reports that the roof of one of his buildings is supported by it. The three surviving wooden receiver towers (one had already been 'dismantled' in 1947 when an Anson mailplane from the Channel Islands collided with it, killing both crew members) were treated with less respect. The nine inch square timbers were sawn through about fifty feet above the base and by means of a very long hawser attached towards the top, each tower was pulled down by a tractor. Some of the timbers eventually became part of the sea defences on the Ventnor front. Within a week all six towers had gone, but the sixteen large concrete footings of the receiver towers remain to this day. This work by a London contractor, W.Habron & Co., was initiated in January and should have been completed by Easter 1957. The photo on the left appeared in the County Press and has been supplied by Alan Stroud, author of his recent book "Taken from Yesterday's Papers Vol 5". Interestingly the bungalow guardroom appears in the background so one wonders whether in theory the photographer had unwittingly committed a treasonable act?

The then somewhat seedy establishment off the promenade mentioned above was, if my memory serves me correctly, called Studt's Amusements. It continued to exist as 'The Gaiety', without the dodgems and associated din I'm pleased to say, but in September 2015 I found it to be closed and boarded up, presumably awaiting demolishment. Today, Richard Studt, the son of that establishment and a resident of Ventnor, performs to world class standards on his Stradivarius violin and in addition to at times conducting various orchestras, he runs the strings ensemble The Sinfonietta, (the Bournemouth Sinfonietta reborn, I believe) which several times each year, he brings to the Island together with top solo classical performers to delight audiences of over 500. How ironic and right it is that such incredibly sweet music should now arise out of the proceeds engenerated by that earlier raucous din. By chance I had a brief opportunity to mention this to Richard at one of the concerts and he laughingly told me that as a teenager he was frequently employed in collecting the money from the dodgem customers.

Everybody who served at RAF Ventnor will remember Peter Cortesi the cheerful shoe repairer and his tiny shop at the top of The Shute. I am happy to report that he is alive and well and now living in a retirement home in Ventnor. Peter was an Italian and came to the Island as a prisoner of war, one of the many thousands who surrended in Libya in the early years of the war. He met his wife-to-be working on a farm at Niton and didn't want to go home in 1945.

Steve duly married Shirley and was posted to RAF Trimingham. After demob he worked for Plessey Radar at Cowes as a draughtsman. They lived at Shanklin until Steve died in 2011.

Text © 2006 D.C.Adams

Rev 041015