A good chunk of north eastern Libya was within our range but the area of interest was our eastern sector i.e. the one towards Palestine and Cairo airport although we could not see as far as either of those. Our Operations people were aware of all scheduled air movements so any additional targets seen were of intense interest and were reported to a higher authority, probably back in the UK. However, there were very few such echoes to report and after a few weeks we were all able to relax and to begin to wonder whether our presence was really necessary after all.

But one day there was a real flap. A target was flying westward towards Libya from the east five miles inland from the coast. Normally at that time a commercial flight should have been on the same course but five miles out over the sea. He was requested by radio to move out but did not answer. Our drill at this point was to call for an inspection of the target by fighter planes based in Cyprus, but on this occasion another course of action was followed. The previous day, the Display Squadron of Hunters known as the Black Arrows had refuelled at El Adem as they returned from India. One had remained behind to have a minor fault fixed, but was now operational and back on the tarmac after a short test flight. He was scrambled and within minutes was with the target which then promptly put itself back on to its scheduled course. It was merely the commercial flight we expected it to be, but you can imagine the consternation of its crew and passengers as the Hunter performed close passes and reportedly, aerobatics around them. This incident was about the most exciting thing to happen, and whether any real 'enemy' activity was detected or not was never revealed to me. Accordingly I am unable to make further comment on operational activity.

Apart from early morning Daily Routine Maintenance, when the heads had to be checked for correct transmitter adjustment and receiver tuning, there was little for the technical people to do. When on duty we just waited for something to malfunction. At nights I would sleep across the seats in the cab of the Workshop vehicle, and was rarely called out. During the days we might play darts, cards or volley-ball or just chatter in some corner of shade. As the weeks dragged on the temperature became a little more bearable but in the autumn we often suffered from mini-tornadoes of swirling dust (ghibli) though we never had a fully fledged sand storm.

One problem gave concern for several weeks. The fan belts on the Lister diesels started breaking, but as each engine had three in parallel pulley grooves, if one was broken this was not an instant disaster. However, if two were broken we were living dangerously as two generators were essential if all the heads were powered up. We soon ran down our stock of spare belts and replenishments had to be flown out from the UK. On one occasion we heard that a Beverley had made a special trip to bring another dozen belts. Our MT people could find no reason for the breakages and after a while the problem became more infrequent until it ceased to be a worry.

We heard that it was possible to go on 'flight experience' trips so three of us requested to do so, and one morning immediately after breakfast we picked up parachutes from the store and reported to the Control Tower. We were told that we were late and that the kite was already moving to the end of the runway, but that the fire engine would take us out to it. We soon caught up the high winged twin engined Pembroke, which paused, the door opened and we climbed into the last three seats of about nine. As we flew low over the desert we could see that vast areas looked like a lunar landscape, this being caused by the exploding mines. We quickly reached the coast and the pilot began inspecting all the small sea inlets in the cliffs and we realised that this was his mission, the flight was not just a joyride. Eventually after drawing many blanks he found a moored native sailing boat. The pilot carried out a series of alarming dives down upon the craft, zooming between the cliffs and twisting the plane over as he skimmed across the water to allow his companion at the front to photograph the boat. I don't know who was worried the most, the crew of the boat or the passengers in the plane.

During one afternoon, when in German Town off duty, we witnessed an unusual bit of flying. There was a daily 'milk-run' flight made by a civilian Viking belonging to a company called Eagle Airways, linking many of the coastal towns in that part of the world. On this occasion, when it took off from Benghazi something fell from its undercarriage but it flew on to us having managed to get the wheels up OK. At El Adem they were lowered again and while it made several low passes the undercarriage was inspected from the ground through binoculars by the Control Tower people. The decision was made that it should do a wheels-up landing on the old dirt runway. This it duly did and we had a perfect view as the plane flew down to zero feet until the propellors bit into the ground. It stopped in a short distance and as the following fire engines reached it, the door opened and about twenty people jumped out and lined up some distance away to be counted. I have often wondered what would have happened if it had had to land on concrete. About a week later we heard that it had flown off after having been strengthened internally, fitted with new propellors and presumably with a repaired undercarriage.

During one period, Vulcan bombers arrived and practised 'circuits and bumps'. These very noisy aircraft did this mainly in the evenings, often until midnight. We sometimes played a very silly game when returning from an evening's drinking in the NAAFI, when our route took us around the peri-track to German Town. At the point where the flight path crossed the perimeter, we would wait for the next bomber to take off after its 'bump'. As the huge bulk roared on full power a few feet over our heads, he who first clapped his hands over his ears was declared 'chicken'. I am now thankful that it was usually me.

Bombers also visited the bombing range a few miles from El Adem. The fall of their bombs had to be plotted and we heard that the observers were usually people who had committed some small misdemeanour and were sentenced to do a number of days of this duty at the range.

We worked the three shift system right through to mid December when we were 'stood down' and accordingly trips to Tobruk and the sea were very infrequent as our off-duty periods rarely matched availability of transport. Life was made much more pleasant however by the weekly visit to the camp of two Salvation Army ladies, one a portly old dear who closely guarded her more nubile teenage companion. They ran a newspaper stall in the foyer of the Cookhouse and we were able to purchase monthly magazines and newspapers only a week out of date.

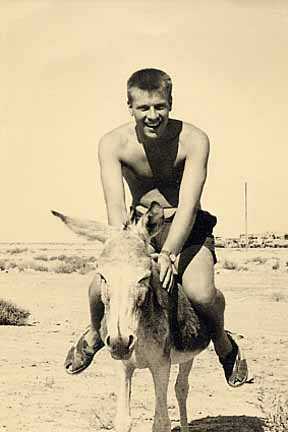

Finding myself tending towards the onset of 'ElAdemitis', I decided that I needed more contact with people back home, so I bravely penned a tentative letter to my ex girlfriend in the Isle of Wight, enclosing this photograph of me bestride a donkey. She was very surprised to hear from me, but cheerfully corresponded regularly, which lifted my spirits more than somewhat, and a comforting feeling grew that I would be meeting her again one day.

Finding myself tending towards the onset of 'ElAdemitis', I decided that I needed more contact with people back home, so I bravely penned a tentative letter to my ex girlfriend in the Isle of Wight, enclosing this photograph of me bestride a donkey. She was very surprised to hear from me, but cheerfully corresponded regularly, which lifted my spirits more than somewhat, and a comforting feeling grew that I would be meeting her again one day.

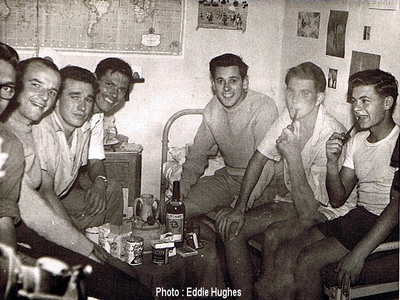

We managed gradually to improve our accommodation by making odd bits of furniture from packing cases and painting out our room in tasteful tints created from small amounts of fire-engine red, drab olive, or desert beige mixed with lots of gloss white. There was always plenty of white paint available anywhere in the RAF. Also, very much earlier our electricians had installed in each room a single 60 watt light and switch. The electricity for these came from the mobile petrol-electric set belonging to our Workshop vehicle which was removed and set up in a spare hut, and we were allowed to have this running from dusk until 22.30. Dick Holmes has reminded me that we enjoyed the curiosity of our room behaving as a camera obscura due to a knot hole in the door. In the dark interior we could see on one wall the upside-down images of people walking past in the brilliant sunshine.

Life was not improved by an unusual occurrence that affected the whole camp from the Group Captain downwards. A new consignment of the drinking water that reputedly came by ship from Malta had been treated to an excessive amount of chlorinated bug-killer. It was almost undrinkable and all the vegetables served in the Cookhouse were equally unpalatable, likewise tea and coffee. And this was the water for which we had to pay by virtue of half of our overseas allowance being deducted! We suffered this for about two months and the only palliative was to mix sufficient Quosh to neutralise the chlorine in the drinking water we carried in our bottles.

In general the food wasn't very good or plentiful at El Adem, varying from almost passable to downright awful, and not helped by what I detected as a "don't care" attitude from the cookhouse staff. Not that one could blame them really, it must have been sheer hell working in the kitchen, especially slaving over a chip frier, and that is probably why a dollop of Pom potatato was usually served. I remember that one day there was a notice stating "There is no bread, so don't ask for it". At one time, "pudding" was just a few grapes every day.

Soon after we had arrived, much to our surprise, each had received an issue of cigarettes. Seized Customs slabs of 200 were passed around and even non smokers such as myself began puffing away. However, a pipe smoking Taffy scorned the cigarettes and he encouraged everybody to try a pipe. I did, and quickly appreciated the difference and the advantage of having an aromatic cloud of Balklan Sobranie surrounding one on the daily visit to the uncongenial toilet accommodation.

I did, and quickly appreciated the difference and the advantage of having an aromatic cloud of Balklan Sobranie surrounding one on the daily visit to the uncongenial toilet accommodation.

Also at this time we began to notice a shortage of plates at the Cookhouse. No longer was there a pile waiting for use at the start of the servery. It was necessary to take some used ones and wash them before it was possible to eat. The reason for this became obvious when somebody looking for plates spotted the cook's assistant's novel way of performing his duty as plate washer. Instead of stacking the crockery in wooden trays to facilitate its progress on a moving belt through the washing machine, he was skimming the plates one after another into the machine's bowels. Of course more came out broken than whole. The man was obviously mad, but it might be more charitable to say that he was suffering a bout of El Adem syndrome, the severity of which was proportional to the length of tour remaining and was a mixture of boredom and hopelessness brought on by the very nature of the place, causing symptoms which manifested themselves in different ways according to the resilience of the individual.

One day when being driven past the Station Sick Quarters we noticed that the building had acquired a strange very large blue box. This wheel mounted device was equipped with a small engine and large diameter pipes led from it and through an adjacent window of the Sick Quarters. On making enquiries we were told that the appearance of this thing meant that 'somebody was dead'. It transpired that this 'Comet Cooling Unit' doubled up as a corpse cooling unit as required. It seemed that on this occasion a sufferer of ElAdemitis had inadvertently killed himself whilst racing in madcap fashion in an 'old-banger' through the scrubby bondu (desert), when it had overturned and being open-topped, the fixed windscreen had unfortunately decapitated him.

The sole barber on the camp was, unusually, a serving member of the RAF and as such took his entitlement of a fortnight's home leave. A notice in his shop had given due warning, but many people failed to have their hair shorn before he went. The SWO and SPs must have been apoplectic, the time honoured shriek of 'Get yer 'air cut!' being meaningless for the next fortnight and it was a month before the regulatory crop was restored to all.

One individual whose nickname might have been 'Gappy' thought that it would be nice to take photographs at our radar site. We watched in amazement as he went around photographing every bit of the equipment, having scorned advice from all sides that he ought not to. To his surprise but not ours, a few days later the photographic shop in Tobruk 'lost' his film. Some of us discussed what should be done, to tell our officers or to keep quiet. It was argued that as our equipment was of an old design, any serious enemy would be well acquainted with its capabilities and this might be a deterrent to any would-be invader. Thus we chose to let sleeping dogs lie, but Gappy was a very worried man for a few weeks.On one occasion this same man was on night guard duty at the site. As I was returning from a Type 13 in the small hours after making a tuning adjustment, he challenged me and because we could not see each other in the gloom, I laughingly called out who I was and told him not to be silly, it was only me and explained briefly where I had been. However, he repeated the challenge and I heard him work the bolt of his rifle. I stood very still indeed and asked him in God's name to point his rifle at the sky. He told me to advance to be recognised or else he would shoot. Seriously worried I said I would only if his rifle was pointed upwards and slowly moved forward. When at last we could see each other I saw that to my horror he had not done as I had requested. The idiot said "Oh it is you then." and only then raised his rifle. I wasn't much in the habit of swearing at people, but I certainly told that bloke his fortune!

Another incident concerned a not very bright weedy young Boy-Entrant from our small MT section. One version of this story suggests that it was his mates who suggested to him that if he wanted the services of a 'professional lady' all he had to do when he was next in Tobruk, was to expose himself to any woman that he encountered. A second version tells that having received a 'Dear John' letter he thought that by getting himself arrested he would be sent back to the UK where he could sort out the problem with his girl friend. Either way he carried out his ill advised action, but his chosen target happened to be an officer's wife. At the subsequent court martial he was sent to a Services prison in Cyprus. He returned in December a changed man. He was about six inches taller and no longer a skinny weed, and marched everywhere in a most correct military manner. Prison seemed to have done him a world of good.

The biggest annual event at any RAF establishment is the AOC's inspection and this happened even in the desert. The whole camp had to be spick and span without a single grain of sand out of place and a maximum turnout was required at the accompanying parade. In the event I did not appear on the actual parade as one or two vital bits of maintenance were required on the Type 15 and I had managed to convince the aged WO that he needed me in his small team to do this work but I could not get out of the parade rehearsals. Everybody had to march up and down and round and round in a series of near incomprehensible evolutions, and of course it took a bit of practice before most individuals could remember even how to do the basic drill sufficiently well, let alone carry out the necessary extra tricky bits required to impress an AOC. The Group Captain had a special weapon to expedite the learning processes. His wife, reputed to be an ex WAAF Queen Bee, sat on a white charger at the edge of the parade ground. She scanned the proceedings with a professionally exacting beady eye and recorded in a little book the identities of those flights responsible for the worst of the shambles, and then they had to report for additional practice later.

As an antidote to all this, we found that it was possible to take a short holiday by hiring the PSI minibus for a weekend. Thus a dozen of us set out for Derna, a town a hundred miles to the west similar in size to Tobruk and reached by a good but narrow tarmac road running parallel with the coast. Our objective was Cyrene, the site of first an ancient Greek and then a Roman holiday resort and its associated corn exporting port of Apollonia.

After several hours of driving with only an occasional hamlet to pass through and virtually no other traffic, we stopped to examine a section of a large Roman irrigation pipe: 2000 years ago this was an extensive corn growing area. Soon after this the road began to climb and we found ourselves on a large fertile plateau with, of all things, greenish fields. Not quite like England, but the first green fields we had seen since arriving in Libya.

Then over the escarpment there below was Derna and the sea. We were to stay in a small hostel, but for our dinner we were directed to a back-street cafe. Here we chose liver and chips but there was some delay before the owner-cum-chef started cooking the meat in frying pans on half a dozen Primus stoves which were arrayed at one side of the dining room. It became obvious that the man was an artist in this work, as like a plate-spinning performer he dodged from stove to stove, pricking a jet here and turning the meat there, to keep them all cooking simultaneously. Eventually we enjoyed a delicious meal, but on leaving the cafe the comfortable feeling was somewhat dispelled as we noticed a small boy leaving the back entrance struggling under the load of a donkey's head.

The next day we left the simple but clean hostel and after about twenty miles we arrived at the ruins. These were extensive and magnificent, the Roman buildings being a little inland from the sea, whilst the remains of Apollonia were on the beach and mostly sea washed. We became surrounded by the usual bunch of kids demanding 'backsheesh'. An LAC from Birmingham handed out a few coppers after he had rehearsed them in bellowing out 'Up the Villa'. I like to think that the descendants of those kids still go around shouting this football battlecry to the amazement of latterday tourists.

On the journey back to the camp we stopped for tea in Derna at the only 'posh' hotel. It was a rather different experience to the donkey café.

The weeks dragged by with few excitements and we began to wonder whether there was really any point to our further presence at El Adem. Then an incident occurred that triggered some of the lads into requesting their parents back at home to ask the same question of their Members of Parliament.

It happened that the Libyan workers enjoyed the occasional bank-holiday, and an Easter-like weekend came along when they did not work on a Friday or Monday together with the usual Saturday and Sunday off.

The already described toilet facilities, although primitive, were acceptable if emptied daily especially since I had taken to smoking my pipe when visiting the toilets, thus insulating myself in a fragrant Balkan Sobranie smoke cloud, and thus oblivious to any off-aromas from the half filled bins. This ploy was ineffective by this particular Sunday and not a single usable bin was to be found throughout Monday, as they were all brim full and overflowing. Local complaints were pointless, those who made them just being told to 'stop binding' and to learn to take a joke. Quite naturally this foul experience affair was reported home by post.

Our domestic quarters were inspected each Friday morning and we liked to think that 'Leeming Lodge' was a cut above the others due to the way we had decorated it and made it comfortable. By this time I had even fixed up a Heath Robinson electric door bell. This was probably the reason that the high ranking Naval officer who was sent to find if our complaints were justified was conducted to see our room as our CO would know that it was one of the best. However this was on a Tuesday, not a Friday, and unhappily was not up to our Friday standard. A bucket stood in the middle of the floor surrounded by odd bits of dhobi work, some washed, some dirty. An opened packet of butter and some burnt toast were by the side of the Primus, and a few empty beer cans were there too. Our semi-inebriated visitors of the previous evening had interrupted a dhobi session and we had slept late leaving no time to clear up in the morning.

As senior man in our room I was responsible for this neglect and when the three of us were hauled before the livid CO the next day I was quite expecting to be severely punished. But I found that I was not on a charge and merely received an intense bollocking. All I could do was stammer an apology for the embarrassment I had caused him and accept responsibility for the disgrace. He was not mollified and suggested that my failure would probably bring the 'Get us Home' campaign to an end. Tactfully I did not voice my contrary view that the inspecting officer had indeed seen that we were required to live in virtual squalor. The CO dismissed us, saying that he would review our fate.

I heard little more about the episode, but the news came eventually that every effort would be made to get our unit home for Christmas. I later learnt from Sergeant Stanbrook that it was only our previous regular high standard on hut inspection that had saved us from punishment, and also that I had once acquired merit in the eyes of the CO for solving a technical problem that had defeated all others when the Type 14 would not sector-sweep, but only continuously rotate counter-clockwise. When I came on shift divine inspiration caused me to blow invisible dust from the vital but tiny air gap of the all important Carpenter relay which was the interface between intricate electronics and heavy electrics. The thing was happily sweeping again within ten minutes after it had been unserviceable for several hours.

And so the Unit did get home for Christmas, well, most of them anyway. A sergeant and two J/Ts had to remain behind to look after the kit until permanent replacements could be sent for this 'care and maintenance' duty. Yes, Sergeant Stanbrook was i/c of me and a Consoles fitter called Colin, and we waved farewell to the rest of them about a fortnight before Christmas.

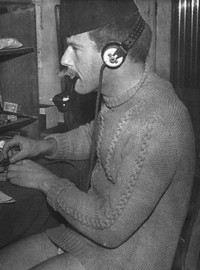

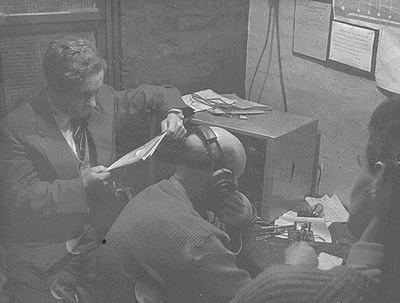

We were not allowed to go on living in German Town but were expected to live in tents on the main camp. However, I knew several of the permanent staff, having met them at the Amateur Radio Club. They lived in one of the large barrack blocks, and we were invited to live with them, sleeping in the beds belonging to people who were on leave in the UK. Only a properly licenced operator was authorised to use the Panda Plus transmitter at the Radio Club and I was impressed by the ease of communicating around the world. One member, an old SAC, would use Morse when the background noise levels rose to prevent voice contacts. His speed on the key was amazing, but his job for the RAF was HF-DF operator which involved him in listening-out all day for semi-lost kites calling from extreme range. He would then keep transmitting to them in Morse until they could get some sort of directional fix on his transmission by rotating a special aerial on the plane, thus enabling them to at least proceed in the general direction of that required.

Only a properly licenced operator was authorised to use the Panda Plus transmitter at the Radio Club and I was impressed by the ease of communicating around the world. One member, an old SAC, would use Morse when the background noise levels rose to prevent voice contacts. His speed on the key was amazing, but his job for the RAF was HF-DF operator which involved him in listening-out all day for semi-lost kites calling from extreme range. He would then keep transmitting to them in Morse until they could get some sort of directional fix on his transmission by rotating a special aerial on the plane, thus enabling them to at least proceed in the general direction of that required.

Back at our radar site there was little technical work to do, but we went through the motions by running up all the equipment five days each week, while the RAF Regiment guarded the dormant gear at night. With a minimum of coaching from Colin I learnt to drive the Landrover and unofficially enjoyed its use around the site and just for fun I sometimes moved the water bowser with its 'crash' gear change, about too.

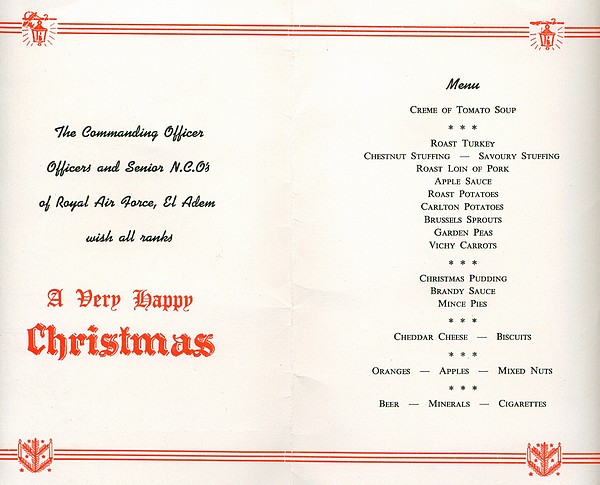

My 21st birthday arrived and I celebrated this with Colin in the NAAFI by consuming an excessive quantity of Watney's Pale. Then it was Christmas day, and the Officers did serve the Christmas dinner in the traditional way. The Group Captain made a short speech, finally announcing that the swimming pool would be constructed in the coming year. The occasion was quite spoilt when an anonymous voice yelled from the back "That's what you said last year you silly old f**t!"

New Year's eve arrived and 1959 was seen in with a tradition which embraced the El Adem syndrome. For that one evening only, glasses were available in which to decant the beer: until then it had always been a case of drinking straight from the can. But on the stroke of midnight, with a mighty cheer, the year's supply of glasses were thrown at the walls until not one remained unbroken.

Finally, in the middle of January our unfortunate replacements arrived and we sympathetically showed them around the camp and the radar site. Two days later I was dressed in best blue and waiting with my kit bag and suitcase at the Control Tower for a flight home: pot-luck would decide the sort of kite that would convey me, and I was dreading that it would be a Beverley, which were about as comfortable as a pantechnicon and were reputed to lose at least one engine on every flight.

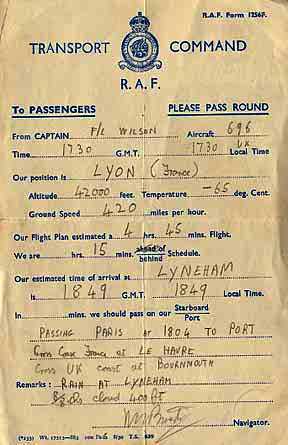

Then there came down out of the sky a great big beautiful Comet, and apart from the smell of ether, as it was a 'Cas-Evac' flying ambulance, and by avoiding eye contact with the unfortunate incapacitated other passengers, sitting on a 'jump' seat near the tail, I had an uncomfortable but fast flight home. There was a period of high anxiety due to eight-eighths cloud and driving rain at Lyneham, which we penetrated only at the third attempt.

Inadvertently I made a foolish mistake at Customs by being the last one of the few ambulatory passengers to pass through. They must have had a sparse haul from those preceding me, as they clobbered me with £12 duty on my new Braun Paxette camera. At midnight I arrived eventually at Oxford railway station where the solitary taxi had to be bribed to take me to Sutton Courtenay through rain and floods. My parents had moved there whilst I was in Libya and it was only by disturbing a couple in a steamed up car for directions, that I could find my way to the correct street and to the light left burning in the hall of my new home.

There is a postscript to add concerning the fate of 425 SU. It was still on Care & Maintenance in August 1960 when Allan Brooks was posted to El Adem to help perform that duty. He found it just where I had left it eighteen months previously. During his time the Unit never returned to operational status and Allan spent much time in repeatedly painting everything. First by replacing the drab olive with the more normal Desert Sand and then with RAF Blue. However the taste of the MEAF top brass continued to change and the Sand colour was required again before they finally settled on blue. In early 1962 all was de-installed and sent to Kuwait. An example of bad planning was encountered when it was found that some vehicles were too wide to fit the provided ship's doors. A few months later a new Convoy arrived and Allan installed that by the internal peripheral road from the Control Tower to German Town and was still there on Care & Maintenance in August 1962 when Allan managed to escape back home. I am hopeful that he will provide further details in due course.

425 SU eventually ended up at RAF Labuna in Borneo where no doubt it carried out an important role in the war against President Sukarno. This site records that 425 SU was there in December 1964.

If you haven't found them already, an additional Page of Pictures exists.

And another provided by Eddie Hughes. Also we now have Dick Holmes' Memories.

Here is a page listing some of the 425 SU Personnel

Return to Leeming...or...Return to first El Adem page...or...Return to second page

Another little postscript : Although the old camp is now a Libyan military base, a party organised by TEARS (The El Adem Radio Service reunion group) were allowed to visit it and were made most welcome.

Google Earth provides an excellent satellite view of the camp.

Text & Picture © 2006 D.C.Adams

Rev220520p>